Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum Urban Waterways Newsletter

By Hyon K. Rah, Summer 2015 Issue

The role of urban waterfronts in industrialized countries used to be a mere vehicle for moving goods and materials and a resource for water-intensive industries. While there was no arguing their economic value, urban waterfronts were gloomy, stinky corners of town people wanted to avoid.

They have come a long way since then. It is almost impossible for us to picture, for example, the delightful Inner Harbor in Baltimore as derelict, post-industrial wasteland it used to be only a few decades ago.

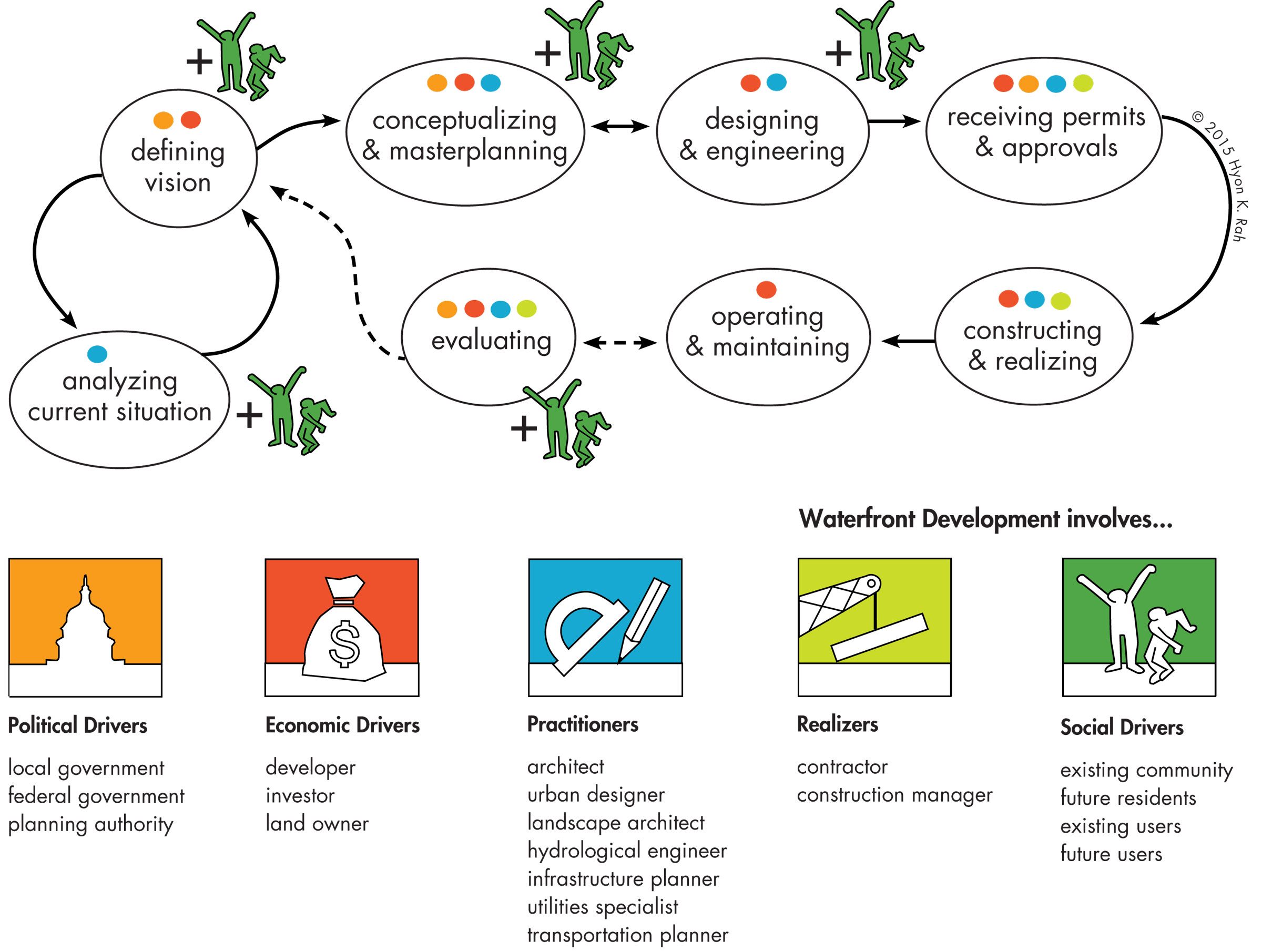

As one could imagine, planning and implementing such a development is not exactly a walk in the park. It is a complex process that involves a multitude of stakeholders, such as those who set the tone through a framework/policy (i.e., city officials), fund the development (i.e., developers), and solidify the vision for the project (i.e., urban designers, architects, engineers). As a designer and an engineer, one of the most important things for me in navigating this process has been to understand what drives the key players; it is easier to get through to people when you connect to them based on the things they care about. It is a delicate dance. On one hand, you have to be clear about the motivation of those who set regulatory and budgetary boundaries for the project so you can keep moving forward. On the other hand, you need to clarify the project goals and priorities with practitioners from related yet different backgrounds, which is a huge challenge. When orchestrated right, however, it results in an amazing collaborative effort towards a shared goal. It also comes with surprising moments of enlightenment. I still remember the shock of realizing that someone might actually care more about the capacity of the water pump than the look and the feel of the water feature it served – it was an eye-catching centerpiece I was sure no one would miss! But I digress.

To add even more to this already complicated matrix seems absurd, and explains why the feedback and the input from the end users for which the space is developed is consistently absent from the actual practice. Somewhere in the midst of catering to the clients’ wishes, balancing the project budget, and juggling the different disciplinary priorities, the need of the actual users of the space starts appearing as an inconvenient burden that can simply be shelved away. Still, the lack of community representation in defining the vision for the waterfront is something I have always found troubling. Why should the people who are directly affected by the new development not have more say in how it unfolds? What happened to equitable development? Who is the development actually for?

Following the many precedents where the polish of the newly developed waterfronts replaced the existing character unique to the location and, eventually, displaced the community itself, the “how” of community engagement has been in the spotlight for some time. Different ways to encourage early and continuous community engagement for waterfront developments have been formulated and shared to best reflect the will and the need of the community, while collaboratively exploring what comes after the development.

So what is the problem, one might ask. True, there are many ways in which the community can have a hand in the direction of the development. Incorporating a sense of place to each new development by drawing from the history and the spirit of what already exists also makes a lot of sense, in theory.

The disturbing truth is that the main motivations that drive these developments, namely political and economical, do not align with encouraging community engagement. In an era where external agencies and organizations are constantly rating individual cities on their destination-worthiness, rejuvenated waterfronts make for glamorous showcase pieces for a city, and the human dimension and sense of place do not photo-graph very well. An-other factor is the economics behind the development. A once-through, “big bang” style of development tends to yield the fastest payback for the investors, and such an approach has proven economically successful in many cases. So what would be the incentive for adding more to it?

Until this issue of alignment is resolved, it will be difficult to see the political and economical drivers reaching out to the community as a priority. So, perhaps, the real question I should have been asking all along, before getting ahead of myself with how to engage the community, is this: How do we make community engagement pencil out?

To see the original article on Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum’s Urban Waterways Newsletter (pp.4-5), click here.